Comanche Jack” Stilwell is

Comanche Jack” Stilwell is  so prominently reported throughout the country that Jack became famous before Buffalo Bill Cody achieved a large degree of attention—Cody wouldn’t receive the Medal of Honor until 1872.

so prominently reported throughout the country that Jack became famous before Buffalo Bill Cody achieved a large degree of attention—Cody wouldn’t receive the Medal of Honor until 1872.

Wild Bill Hickok’s career was still young at the time; only the year before, 1867,Harper’s gave him international  recognition. Stilwell was better known in his own time, but he never reached the heights of Cody, Hickok or any dozen

recognition. Stilwell was better known in his own time, but he never reached the heights of Cody, Hickok or any dozen other Old West characters who have retained their fame into the 21st century.

other Old West characters who have retained their fame into the 21st century.

recognition. Stilwell was better known in his own time, but he never reached the heights of Cody, Hickok or any dozen

recognition. Stilwell was better known in his own time, but he never reached the heights of Cody, Hickok or any dozen other Old West characters who have retained their fame into the 21st century.

other Old West characters who have retained their fame into the 21st century.

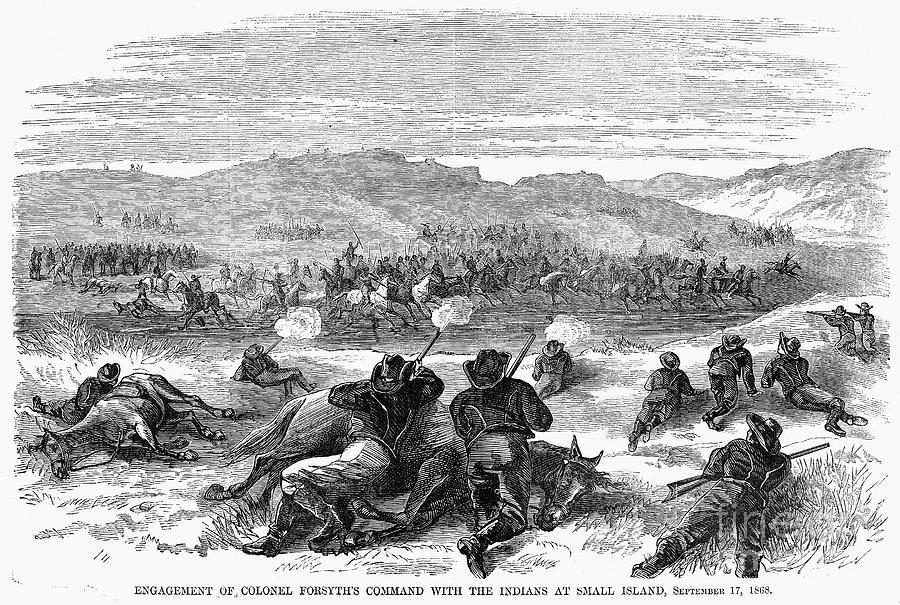

In the annals of the American West are accounts of innumerable battles between settlers and American Indians. For  many students of the Indian Wars, three battles stand out above the rest: Little Big Horn, Washita and Beecher Island.

many students of the Indian Wars, three battles stand out above the rest: Little Big Horn, Washita and Beecher Island.  Though the Beecher Island affair does not today have the acclaim of the other two, it stands as one of the most significant displays of frontier courage in military history.

Though the Beecher Island affair does not today have the acclaim of the other two, it stands as one of the most significant displays of frontier courage in military history.

many students of the Indian Wars, three battles stand out above the rest: Little Big Horn, Washita and Beecher Island.

many students of the Indian Wars, three battles stand out above the rest: Little Big Horn, Washita and Beecher Island.  Though the Beecher Island affair does not today have the acclaim of the other two, it stands as one of the most significant displays of frontier courage in military history.

Though the Beecher Island affair does not today have the acclaim of the other two, it stands as one of the most significant displays of frontier courage in military history.

America’s Original “Rough Riders”

The name “S.E. Stilwell” first appeared on the Quartermaster’s Records at Fort Dodge in Kansas in March 1867, when Jack was 16, almost 17, years old. He entered service as a “laborer,” but by June, he was listed as a scout under Maj. Henry Douglass’s command.

Frontier scouts, like interpreters, guides and packers, had long been a staple in the military. They were non-soldier employees who the Army usually hired month by month. When Gen. Philip Sheridan authorized Maj. George A. “Sandy”  Forsyth to try a new scouting tactic, raising a company of 50 “first class handy frontiersmen to be used as Scouts against the hostile Indians,” 18-year-old Jack readily signed up, on August 24, 1868.

Forsyth to try a new scouting tactic, raising a company of 50 “first class handy frontiersmen to be used as Scouts against the hostile Indians,” 18-year-old Jack readily signed up, on August 24, 1868.

Forsyth to try a new scouting tactic, raising a company of 50 “first class handy frontiersmen to be used as Scouts against the hostile Indians,” 18-year-old Jack readily signed up, on August 24, 1868.

Forsyth to try a new scouting tactic, raising a company of 50 “first class handy frontiersmen to be used as Scouts against the hostile Indians,” 18-year-old Jack readily signed up, on August 24, 1868.

These scouts, America’s original “Rough Riders,” were first known as the “Solomon Avengers” and soon as “Forsyth’s Scouts,” in honor of their commander. Of the 50 total scouts, 30 were enrolled at Fort Harker and 20 more at Fort Hays.

Within five days of their enrollment, the column left Fort Hays for a scout in the area of the Solomon River where Indian depredations had resulted in the deaths of several settlers. Finding no Indians, the scouts rode farther west to Fort Wallace, arriving there on September 5.

During five days rest, the scouts organized needed supplies. On September 10, they were all set to rescue some settlers between Bison Basin and Hardingens Lake when word came of an Indian attack in Sheridan, Kansas. From Sheridan, Forsyth’s scouts followed the trail northwest for five days, a trail which led up the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River and into Colorado. On September 17, they began the Battle of Beecher Island some 17 miles south of the present-day community of Wray in Yuma County.

and Hardingens Lake when word came of an Indian attack in Sheridan, Kansas. From Sheridan, Forsyth’s scouts followed the trail northwest for five days, a trail which led up the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River and into Colorado. On September 17, they began the Battle of Beecher Island some 17 miles south of the present-day community of Wray in Yuma County.

and Hardingens Lake when word came of an Indian attack in Sheridan, Kansas. From Sheridan, Forsyth’s scouts followed the trail northwest for five days, a trail which led up the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River and into Colorado. On September 17, they began the Battle of Beecher Island some 17 miles south of the present-day community of Wray in Yuma County.

and Hardingens Lake when word came of an Indian attack in Sheridan, Kansas. From Sheridan, Forsyth’s scouts followed the trail northwest for five days, a trail which led up the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River and into Colorado. On September 17, they began the Battle of Beecher Island some 17 miles south of the present-day community of Wray in Yuma County.

Jack’s own account of his role in this affair has been rarely told with any detail of his personal exploits. While he occasionally shared his story with friends, he gave few formal interviews. On August 29, 1895, he responded to a letter from Franklin G. Adams of Topeka, Kansas, in which Adams had asked for Jack’s story of the “Arikaree Fight.” Jack stated that he was not in the habit of writing about himself and that most of the articles about Forsyth’s scouts he had read needed to have about a thousand I’s removed.

When Jack told the story of the battle, he did not glorify his part, as was often done by old-timers; rather, he shared a simple, straightforward retelling of the events from his perspective.

The following is a combination of basic information condensed from Jack’s few extant interviews with newspapermen and writers, like Frederic Remington, who called Jack, “My hero.”

Jack Stilwell’s Account

“Along about the middle of September, 1868, Colonel ‘Sandy’ Forsyth was ordered by General Sheridan to hire frontiersmen and start out to overhaul a war party of Brule and Ogallala [sic] Sioux and Dog Soldier Cheyennes which had been raiding the country....

“It was not long after leaving Fort Wallace with our supplies that we struck the trail of the marauders. From the tracks Indians left behind them we judged that there were about 3,000 tepees in the outfit. It was evident that the Indians were making slow progress, owing to their great number and camp truck. We were thus enabled to cover as much ground in one day as they were in two.

“On the night of the 16th we camped on a flat and narrow sandbar. Early the next morning we were attacked by the Indians, who attempted to run off our stock. While we were saddling our horses a large party began a more vigorous fight upon us. The sun was just rising when it was decided that we should move upon a sandbar, which was an island in wet weather....

“We quickly took possession of the upper end of the island, while the Indians swooped down upon the lower end. The fight was now on.

“Colonel Forsyth detailed myself and five other men to go bushwhacking and capture, if possible, the position held by the Indians. This we accomplished, but the Indians had by this time stationed their sharpshooters in the hollows nearby and prevented us from returning to the main body. The fight had lasted an hour and a half when we received the relief that we had sent for....

“At 10 o’clock old Roman Nose, chief of the Dog Soldiers and the most celebrated Indian fighter of that day, assumed command.... The Indians bore down on our center, and, breaking it, dashed almost half way to the main party of our men when a bullet [said by fellow scout Amos Chapman to have been from Jack’s rifle] struck Roman Nose behind and pierced his abdomen...he soon fainted and was borne off the field by his soldiers. A young warrior...relative of Dull Knife now assumed command...[but] he, too, fell dead with a bullet in his head. From that moment the Indians didn’t recognize any commander, but kept up the fight in a haphazard way until after 5 o’clock when they received reinforcements and a new man in command.... At sundown the Indians drew off their horsemen, but left their sharpshooters.

“I then joined the main party and for the first time learned the effect of the fire of the Indians. Colonel Forsyth had both legs broken, Lieutenant [Frederick] Beecher had a broken back and three bullets in his body, and Dr. [John] Mooers had been fatally shot in the head...more than one half our force were either dead or wounded.

“It was nearly midnight when Col. Forsyth ordered old Pete [Trudeau] and myself to make a forced march to Fort Wallace, which was 120 miles away.... Wrapping blankets about ourselves, we crawled out among the Indians....

“Each of us had cut off a chunk of raw horse meat on the way and then with moccasins, made from the tops of our boots and with the rather stinking saddle blankets wrapped around us we made, we thought, fairly representative Indians....

“We succeeded in making three miles the first night. Then we hid ourselves in a washout in a ravine where the grass had grown so tall that it hung over the ledges. Here we lay all the next day listening to the fighting on the island, and yet we were powerless to get the relief we were after or return to our party. We had made up our minds, if we were hailed in Cheyenne, to answer in Sioux, and if hailed in Sioux, to answer in Cheyenne, so that either would be likely to let us pass.

“That night we made more track toward Fort Wallace only to find ourselves within half a mile of the main village of the Indians on the south fork of the Republican. We got into a swampy place and hid during the day....

“The next morning we found ourselves at the head of Goose Creek on a high, rolling prairie. The Indians were so thick all around that we had to hide in the carcasses of two buffaloes.... There was just enough hide on the bones to conceal us.... When night came we pulled out and reached Fort Wallace.

“As soon as we told our story, General Sheridan ordered all available troops to the scene of the fight. Meantime, however, two couriers [Allison Pliley and John Donovan] had reported the fight to [Lt.] Colonel [Louis] Carpenter’s command, and that good old soldier...struck right out and reached the battlefield forty-eight hours before the troops from the fort got there.

“That fight was fought on the Arickaree [sic] fork of the Republican. I don’t know how to spell that word and I never saw a man who did. But that’s the story [John] Burke wanted me to tell you.”

Forsyth’s Heroes

Jack’s published accounts of this great rescue effort never included the famous story of his spitting in the eyes of a rattlesnake, though he did mention hiding in the carcasses of two buffaloes. The “legend” goes that while Jack and Trudeau were hiding, a rattlesnake took up his abode in the same carcass Jack had climbed in. With Indians nearby who would have heard his cry if bitten, Jack spit tobacco juice in the snake’s eyes. The snake slithered off. As the saying goes, “If it’s not true, it ought to be.”

Colonel Forsyth explained why he had selected Jack and “Avalanche” Trudeau to make the first attempt at going for help: “I had volunteers in plenty to go to Fort Wallace, and of these I selected two— Pierre Truedeau [sic], an old and experienced trapper, and a young fellow named Jack Stillwell [sic].... Two better men for the purpose it would have been difficult to find. I gave Stillwell [sic], as he was by far the more intelligent and better educated man of the two, my only map....”

Jack and Trudeau reached the stage road station in Cheyenne Wells, Colorado, about sundown and waited until the stage from Denver came through on its way to Fort Wallace, arriving there on the evening of September 22. Colonel Henry Bankhead wired Jack’s report to Gen. Sheridan.

Although exhausted, Jack insisted on joining Bankhead’s command to witness the rescue. His feet were bruised, sore, dreadfully swollen and stung full of cactus needles and thistles. He bound them up with strips off his blanket and then got in an “ambulance” that transported him from Fort Wallace to the island, a two days journey. Upon arriving, he forgot his condition and rushed to meet his comrades, his eyes filled with tears of joy at seeing those yet alive. Scout John Hurst later described the teenaged Jack during this event as “one of the bravest, nerviest and coolest men in the command.”

The Life of a Courageous Adventurer

Jack had signed on with Forsyth’s Scouts at a pay rate of $75 per month, based on his furnishing his own horse and tack. He received a bonus of $150 for his bravery in the Beecher Island battle.

After several weeks of recovery at Fort Wallace, 17 of the Forsyth Scouts, including Jack, went to Fort Hays. There, on October 20, they were placed on Capt. Amos S. Kimball’s roll. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody recorded in his biography that Fort Hays was where he met and spent a few days with the “survivors of this terrible fight.”

On October 31, Bvt. Lt. Col. J. Schuyler Crosby directed Capt. Kimball to “pay S.E. Stillwell [sic], Scout and Guide now on your rolls, up to and after Nov. 1st, 1868 at the rate of $100 per month from his last payment as one of Forsyth’s Scouts—transferred.”

The pay rate of $100 per month was exceptional, and Jack was one of only three scouts to receive such a fee. Cody, who served under the same command, was receiving only $75 per month.

From their first meeting at Fort Hays, Cody and Jack developed a lifelong friendship. In Jack’s later years, he worked for Cody as a ranch foreman and on behalf of Cody in his fight for water rights in the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming.

Most of the 17 Forsyth scouts transferred to Capt. Kimball, including Jack, were reorganized under the command of Lt. Silas Pepoon. Jack and “Pepoon’s Scouts” were associated with George Armstrong Custer in the winter campaign of 1868 against the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa and Comanche tribes including the Battle of Washita River.

In April 1875, Jack and one other man made a trip into the Staked Plains and induced the Quahada Comanches, under the leadership of Mow-way and Quanah Parker, to surrender. Jack scouted for Custer, Sheridan, Benjamin F. Grierson, Ranald S. Mackenzie, John “Black Jack” Davidson, George A. Armes and numerous other frontier military leaders, many of whom wrote glowing testimonials on his behalf in 1896, when he applied for a military pension.

Jack continued his service to the frontier army into the early 1880s, primarily at Fort Sill in the Indian Territory. During much of his time in the 1870s-80s, he also served as a deputy U.S. marshal, and his exploits in chasing and corralling outlaws are legion.

In 1877, he went with his younger brother, Frank, W.H.H. McCall and others to Fort Whipple in Arizona. There, he served as a packer until he grew dissatisfied with that country, whereupon he went to Fort Stockton and Fort Davis in Texas. In 1882, when Frank was killed in Tucson, Arizona, by Wyatt Earp’s Vendetta Posse, Jack went to Tombstone and Cochise County to avenge his brother’s murder. After several weeks of unsuccessfully hunting the Earps with Pete Spence, John Ringo and other Arizona cowboys, Jack gave up the search and returned to Oklahoma.

In the 1890s, Jack served as police judge of El Reno, Oklahoma, for two terms and as U.S. commissioner in Anadarko for three years. In 1898, at Cody’s invitation, Jack and his bride, Esther, moved to Cody, Wyoming, where he received another appointment as a U.S. commissioner.

Jack died of pneumonia in Cody in 1903, his health broken and his body much crippled with rheumatism from his many years in the saddle on the frontier. His body now rests at Cody’s Old Trail Town under an imposing, yet fitting, memorial.

The West has known few men of the caliber of “Comanche Jack” Stilwell. While his deeds of daring were often recorded in frontier newspapers and turn-of-the-20th-century books, he was never a self-promoter. He never appeared in a Wild West show, and he didn’t participate on the lecture circuit. So it is time that “long may his story be told” put Jack into the prominence he deserves.

sharpshooters

sharpshooters