1861: The Civil War Began

Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860, southern states, outraged at the election of someone with known anti-slavery views, threatened to leave the Union. At the end of 1860 South Carolina was the first slave state to secede, and it was followed by others in early 1861. President James Buchanan struggled with the secession crisis in his final months in office. As Lincoln was inaugurated in 1861 the crisis intensified and more slave states left the Union.

- The Civil War began on April 12, 1861 with the attack on Fort Sumter in the harbor at Charleston, South Carolina.

- The killing of Col. Elmer Ellsworth

, a friend of President Lincoln, in late May 1861 galvanized public opinion. He was considered a martyr to the Union cause. Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth rocketed to fame at a young age, befriended Abraham Lincoln, and became a very early casualty of the Civil War. His violent and newsworthy death only weeks into the conflict made him a martyr throughout the North.

Countless printed images of him, along with cries to "Avenge Ellsworth," helped to spur recruitment for volunteer regiments in the summer of 1861.

While not widely remembered today, Ellsworth received a funeral service in the East Room of the White House, and when his body was transported to New York City he was honored with a lavish tribute at the City Hall.

Ellsworth died shortly after returning to Washington. On May 24, 1861 (the day after Virginia's secession was ratified by referendum), President Lincoln looked out from the White House across the Potomac River,and saw a large Confederate flag prominently displayed

over the town of Alexandria, Virginia.

Ellsworth immediately offered to retrieve the flag for Lincoln. He led the 11th New York across the Potomac and into the streets of Alexandria uncontested. He detached some men to take the railroad station,while he led others to secure the telegraph office and get that Confederate flag, which was flying above the Marshall House Inn.

Ellsworth and four men went upstairs and cut down the flag. As Ellsworth came downstairs with the flag, the owner, James W. Jackson

, killed him with a shotgun blast to the chest. Corporal Francis E. Brownell,

of Troy, New York

, immediately killed Jackson. Brownell was later awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions.

Lincoln was deeply saddened by his friend's death and ordered an honor guard to bring his friend's body to the White House, where he lay in state in the East Room. Ellsworth was then taken to the City Hall in New York City, where thousands of Union supporters came to see the first man to fall for the Union cause. Ellsworth was then buried in his hometown of Mechanicville,

in the Hudson View Cemetery.

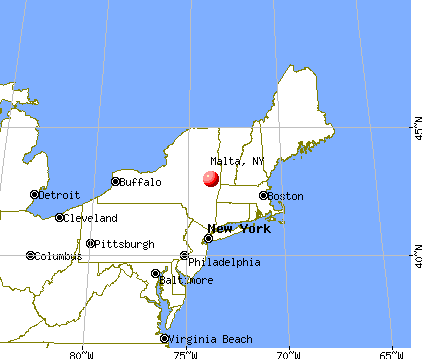

Thousands of Union supporters rallied around Ellsworth's cause and enlisted. "Remember Ellsworth" was a patriotic slogan: the 44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment called itself the "Ellsworth Avengers", as well as "The People's Ellsworth Regiment."Elmer Ellsworth’s life began in obscurity, in 1837, in the village of Malta, New York. He received a minimal education, which thwarted his ambition to attend West Point and become an officer in the U.S. Army.

Educating himself, Ellsworth eventually became a law clerk in Illinois. At a time when American towns often had local militia companies, which were essentially drill teams that performed in parades, Ellsworth became the commander of a militia based in Chicago.

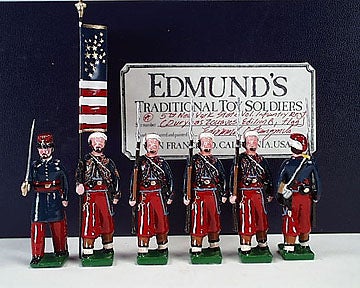

Learning what he could about military tactics and discipline, Ellsworth became fascinated with the French Zouaves, elite infantry soldiers who had fought in the Crimean War. The Zouaves wore elaborate and garish uniforms consisting of brightly colored baggy pants and short jackets. The distinctive uniforms had been adapted by the French from local fighters in Algeria in the 1830s.

Ellsworth reportedly ordered books from France so he could learn everything about Zouave regiments, uniforms, drills, and military tactics. He became convinced that the American military needed units of Zouaves.Ellsworth turned his militia company into a precision drill team dressed as Zouaves. Billed as the "The U.S. Zouave Cadets" they toured 20 American cities in the summer of 1860.

The tour by the Zouave Cadets made Ellsworth a celebrity. With the threat of war hanging over the country, the public became fascinated by the showmanship of the 23-year-old Ellsworth and the dazzling military precision of the Zouaves.

A dispatch in the New York Tribune on August 6, 1860 noted that the Zouaves and Ellsworth had visited Washington's Tomb at Mount Vernon. And while visiting the White House, President Buchanan had invited the Zouaves to perform their precision drills on the south lawn.

By the autumn of 1860 Ellsworth had returned to Chicago, and newspapers were reporting that he was planning to organize other regiments of Zouaves. With war on the horizon, Ellsworth was trying to get the North ready.

And Ellsworth's fame was spreading. A New York Times article in November 1860 noted that Ellsworth had received hundreds of letters asking for information about Zouaves, and to accommodate his fans he had lithographs made detailing the elaborate uniform The first major clash took place July 21, 1861, near Manassas, Virginia, at the Battle of Bull Run.Balloonist Thaddeus Loweascended above Arlington Virginia on September 24, 1861 and was able to see Confederate troops three miles away, proving the value of "aeronauts" in the war effort.

- The Battle of Ball's Bluff in October 1861, on the Virginia bank of the Potomac River, was relatively minor,

but it caused the U.S. Congress to form a special committee to monitor the conduct of the war, a minor affair when compared to later battles in the Civil War. But the disaster for the Union, which took place on the Virginia bank of the Potomac River about 40 miles from Washington, D.C., would have major consequences on the conduct of the war.

A Union colonel killed in the battle,, happened to be a popular United States Senator as well as a longtime friend of President Abraham Lincoln. The Battle of Ball's Bluff, also known as the Battle of Harrison’s Island or the Battle of Leesburg, was fought on October 21, 1861, in Loudoun County, Virginia,

as part of Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's operations in Northern Virginia during the American Civil War.

While a minor engagement in comparison with the battles that would take place in years to follow, it was the second largest battle of the Eastern Theater in 1861, and in its aftermath had repercussions in the Union Army's chain of command structure and raised separation of powers issues under the United States Constitution during the war.

In the weeks preceding the battle, McClellan had been promoted to general-in-chief of all Union armies and, now, three months after the First Battle of Bull Run, was building up the Army of the Potomac in preparation for an eventual advance into Virginia.

On October 19, 1861, McClellan ordered Brig. Gen. George A. McCall to march his division to Dranesville, Virginia, twelve miles southeast of Leesburg, in order to discover the purpose of recent Confederate troop movements which indicated that Col. Nathan "Shanks" Evans might have abandoned Leesburg. Evans had, in fact, left the town on October 16–17 but had done so on his own authority. When Confederate Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard expressed his displeasure at this move, Evans returned. By the evening of October 19, he had taken up a defensive position on the Alexandria-to-Winchester Turnpike (modern day State Route 7) east of town.

McClellan came to Dranesville to consult with McCall that same evening and ordered McCall to return to his main camp at Langley, Virginia, the following morning. However, McCall requested additional time to complete some mapping of the roads in the area and, as a result, did not actually leave for Langley until the morning of October 21, just as the fighting at Ball's Bluff was heating up.

On October 20, while McCall was completing his mapping, McClellan ordered Brig. Gen. Charles Pomeroy Stone to conduct what he called "a slight demonstration" in order to see how the Confederates might react. Stone moved troops to the river at Edwards Ferry, positioned other forces along the river, had his artillery fire into suspected Confederate positions, and briefly crossed about a hundred men of the 1st Minnesota to the Virginia shore just before dusk. Having gotten no reaction from Colonel Evans with all of this activity, Stone recalled his troops to their camps and the "slight demonstration" came to an end.

Stone then ordered Col. Charles Devens of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry (stationed on Harrison's Island facing Ball's Bluff) to send a patrol across the river at that point to gather what information it could about enemy deployments. Devens sent Capt. Chase Philbrick and approximately 20 men to carry out Stone's order. Advancing in the dark nearly a mile inland from the bluff, the inexperienced Philbrick mistook a row of trees for the tents of a Confederate camp and, without verifying what he saw, returned and reported the existence of a camp. Stone immediately ordered Devens to cross some 300 men and, as soon as it was light enough to see, attack the camp and, per his orders, "return to your present position."

This was the genesis of the Battle of Ball's Bluff. Contrary to the long-held traditional interpretation, it did not come from a plan by either McClellan or Stone to take Leesburg. The initial crossing of troops was a small reconnaissance. That was followed by what was intended to be a raiding party. To make matters worse, Stone was not advised that McCall and his division had been ordered back to Washington

On the morning of October 21, Colonel Devens' raiding party discovered the mistake made the previous evening by the patrol; There was no camp to raid. Opting not to recross the river immediately, Devens deployed his men in a tree line and sent a messenger back to report to Stone and get new instructions. On hearing the messenger's report, Stone sent him back to tell Devens that the remainder of the 15th Massachusetts (another 350 men) would cross the river and move to his position. When they arrived, Devens was to turn his raiding party back into a reconnaissance and move toward Leesburg.

While the messenger was going back to Col. Devens with this new information, Colonel and U.S. Senator Edward Dickinson Baker showed up at Stone's camp to find out about the morning's events. He had not been involved in any of the activities to that point. Stone told him of the mistake about the camp and about his new orders to reinforce Devens for reconnaissance purposes. He then instructed Baker to go to the crossing point, evaluate the situation, and either withdraw the troops already in Virginia or cross additional troops at his discretion.

On the way upriver to execute this order, Baker met Devens' messenger coming back a second time to report that Devens and his men had encountered and briefly engaged the enemy, one company (Co. K) of the 17th Mississippi Infantry. Baker immediately ordered as many troops as he could find to cross the river, but he did so without determining what boats were available to do this. A bottleneck quickly developed so that Union troops could only cross slowly and in small numbers, making the crossing last throughout the day.

Meanwhile, Devens's men (now about 650 strong) remained in its advanced position and engaged in two additional skirmishes with a growing force of Confederates, while other Union troops crossed the river but deployed near the bluff and did not advance from there. Devens finally withdrew around 2:00 p.m. and met Baker, who had finally crossed the river half an hour later. Beginning around 3:00 the fighting began in earnest and was almost continuous until just after dark.Depiction of Ball's Bluff by Alfred W. Thopson

Col. Baker was killed at about 4:30 p.m. and remains the only United States Senator ever killed in battle. Following an abortive attempt to break out of their constricted position around the bluff, the Federals began to recross the river in some disarray. Shortly before dark, a fresh Confederate regiment (the 17th Mississippi) arrived and formed the core of the climactic assault that finally broke and routed the Union troops.

Many of the Union soldiers were driven down the steep slope at the southern end of Ball's Bluff (behind the current location of the national cemetery) and into the river. Boats attempting to cross back to Harrison Island were soon swamped and capsized. Many Federals, included some of the wounded, were drowned. Bodies floated downriver to Washington and even as far as Mt. Vernon in the days following the battle. A total of 223 Federals were killed, 226 were wounded, and 553 were captured on the banks of the Potomac later that night. It is interesting to note that the Official Records incorrectly state that only 49 Federals were killed at this battle, an error probably resulting from a mistaken reading of the report of the Union burial detail which crossed over the next day under flag of truce. Fifty-four Union dead—of whom only one is identified—are buried in Ball's Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery.

Aftermath

This Union defeat was relatively minor in comparison to the battles to come in the war, but it had an enormously wide impact in and out of military affairs. Due to the loss of a sitting senator, it led to severe political ramifications in Washington. Stone was treated as the scapegoat for the defeat, but members of Congress suspected that there was a conspiracy to betray the Union. The ensuing outcry, and a desire to learn why Federal forces had lost battles at Bull Run (Manassas), Wilson's Creek, and Ball's Bluff, led to the establishment of the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, which would bedevil Union officers for the remainder of the war (particularly those who were Democrats) and contribute to nasty political infighting among the generals in the high command.

Lt. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, survived a nearly fatal wound at Ball's Bluff to become an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1902. Herman Melville's poem "Ball's Bluff - A Reverie" (published in 1866) commemorates the battle. Holmes' great friend and role model, Lt. Henry Livermore Abbott also survived the battle but did not survive the war. In 1865, Abbott was posthumously promoted to Brigadier General. Another outstanding young officer named Edmund Rice also eventually reached the rank of Brigadier General, was awarded the Medal of Honor and was fortunate enough to survive the war by near a half century. John William Grout was killed in the battle; his death inspired a poem (and later a song) titled "The Vacant Chair".

The site of the battle has considerably overgrown today, though ongoing efforts by volunteers have thinned out the overgrowth and made interpretation of the battlefield much easier. It is preserved as the Ball's Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery, which was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1984. The park is maintained by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Au

No comments:

Post a Comment