Tlhesaesasae First BThe First Battle of Fort Wagner, occurred on July 11, 1863. Only 12 Confederate soldiers were killed, as opposed to the Union's 1330 losses.[1]The first battle of Fort Wagner, occurred on July 11, 1863. Only 12 Confederate soldiers were killed, as opposed to the Union's 1330 losses

Tlhesaesasae First BThe First Battle of Fort Wagner, occurred on July 11, 1863. Only 12 Confederate soldiers were killed, as opposed to the Union's 1330 losses.[1]The first battle of Fort Wagner, occurred on July 11, 1863. Only 12 Confederate soldiers were killed, as opposed to the Union's 1330 losses

The Second Battle of Fort Wagner, a week later, is better known. This was the Union attack on July 18, 1863, led by the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, one of the first major American military units made up of black soldiers. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw led the 54th Massachusetts on foot while they charged and was killed in the assault.Shaw was born in Boston to a prominent abolitionist family. His parents were Francis George and Sarah Blake Sturgis Shaw. The family lived off an inheritance left by Shaw's merchant grandfather, also named Robert Gould Shaw (1776 – 1853). Shaw had four sisters: Anna, Josephine

, Susannah and Ellen.

, Susannah and Ellen.He moved with his family to a large estate in West Roxbury, adjacent to Brook Farm

when he was five. In his teens, Shaw spent some years studying and traveling in Switzerland, Italy, Hanover, Norway, and Sweden. His family moved to Staten Island, New York, settling there among a community of literati and abolitionists, while Shaw attended the lower division of St. John's College, the equivalent of high school in the institution that became Fordham University. From 1856 until 1859, Shaw attended Harvard University, where he was a member of the Porcellian Club, but he withdrew before graduating. He was a member by primogeniture of the Society of the Cincinnati

when he was five. In his teens, Shaw spent some years studying and traveling in Switzerland, Italy, Hanover, Norway, and Sweden. His family moved to Staten Island, New York, settling there among a community of literati and abolitionists, while Shaw attended the lower division of St. John's College, the equivalent of high school in the institution that became Fordham University. From 1856 until 1859, Shaw attended Harvard University, where he was a member of the Porcellian Club, but he withdrew before graduating. He was a member by primogeniture of the Society of the Cincinnati

Although a tactical defeat, the battle of Fort Wagner saw action for black troops in the Civil War, and it

Colonel Robert Gould Shaw led the 54th Massachusetts on foot while they charged and was killed in the assault

and it spurred additional recruitment that gave the Union Army a further numerical advantage in troops over the South

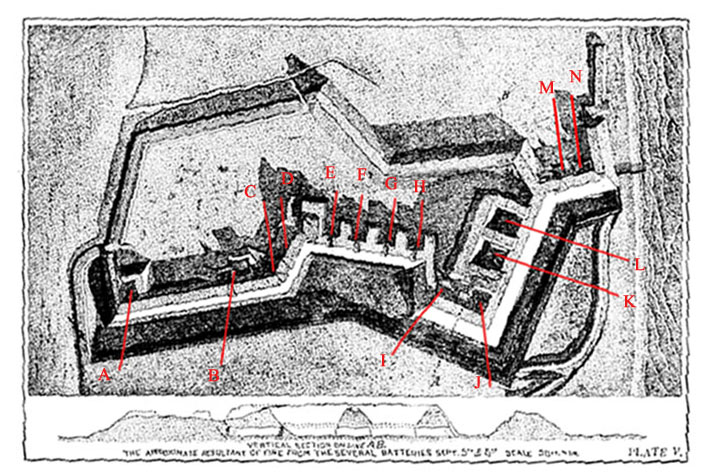

The Union besieged the fort after the unsuccessful assault. After enduring almost 60 days of heavy shelling, the Confederates abandoned it on September 7, 1863.There were diverse units of black soldiers, another was the first carolina below

The main reason the fort was abandoned was fresh water. The bodies of the Union troops (54th Massachusetts and many white troops) were buried close to the fort and the decomposition of the bodies poisoned the fresh water well within the fort. Continuing bombardment and interception of food/water supplies by boat from Charleston made holding the fort difficult.

When the fort was abandoned in September 1863, the CSA forces left behind a large amount of gunpowder in the bomb proof. Two drunk Union soldiers were exploring the bomb proofs and set off the gunpowder, killing and injuring another 300 Union Soldiers stationed within the fort

Robert Gould Shaw initially chose to decline the regiment but a desire to please his mother made him take command, A few days later, Robert announced his engagement to Annie Haggerty.

The two had met just before the war when Susanna, one of Robert’s sisters, invited Annie to a small gathering of family/friends attending the opera. Colonel Robert Gould Shawand Anna Kneeland Haggerty were married on May 2, 1863 in The Church of the Ascension

The two had met just before the war when Susanna, one of Robert’s sisters, invited Annie to a small gathering of family/friends attending the opera. Colonel Robert Gould Shawand Anna Kneeland Haggerty were married on May 2, 1863 in The Church of the Ascension on Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street in New York City. They spent four relaxing days in the Berkshires of Massachusetts before Shaw learned that he’d have to return before the week was out as the Governor had ordered his regiment to leave for the south in less than three weeks. Departure day was eventually set for May 28, 1863. On that day, at 9 am, 1,007 black soldiers and 37 white officers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment began a parade march through the streets of Boston in full dress uniform. Twenty-five-year-old Colonel Robert Gould Shaw rode at the head of the column. members of the 54th. Robert Gould Shaw’s family, including his mother, two of his four sisters and his wife, stood on the second floor balcony of the

on Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street in New York City. They spent four relaxing days in the Berkshires of Massachusetts before Shaw learned that he’d have to return before the week was out as the Governor had ordered his regiment to leave for the south in less than three weeks. Departure day was eventually set for May 28, 1863. On that day, at 9 am, 1,007 black soldiers and 37 white officers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment began a parade march through the streets of Boston in full dress uniform. Twenty-five-year-old Colonel Robert Gould Shaw rode at the head of the column. members of the 54th. Robert Gould Shaw’s family, including his mother, two of his four sisters and his wife, stood on the second floor balcony of the  port of Hilton Head. A week later, the 54th took part in a raidthat involved

port of Hilton Head. A week later, the 54th took part in a raidthat involved burning the town of Darien, Georgia

burning the town of Darien, Georgia – something that upset Colonel Shaw greatly. When Shaw learned in late June that his black troops would receive pay of only $10 per month instead of the $13 per month they had been promised (the same as white troops), he protested personally. The men vowed to accept no pay at all until the issue was resolved – and it eventually was, but not until nearly 18 months passed. Concerned that his men might not see any real action and have the chance to prove themselves, Colonel Shaw wrote to General George Strong

– something that upset Colonel Shaw greatly. When Shaw learned in late June that his black troops would receive pay of only $10 per month instead of the $13 per month they had been promised (the same as white troops), he protested personally. The men vowed to accept no pay at all until the issue was resolved – and it eventually was, but not until nearly 18 months passed. Concerned that his men might not see any real action and have the chance to prove themselves, Colonel Shaw wrote to General George Strong on July 6 and asked that the 54th Massachusetts be placed under his command. This occurred a few days later and the regiment performed very honorably in its first major engagement at James Island, South Carolina on July 16. Shortly after the battle, the 54th began a two day excursion with only the hardtack they carried in their packs for food. Marching through mud flats and marsh, through thunderstorms and in the blazing sun, with the aid of two transports they made it to Morris Island on the afternoon of Saturday, July 18, 1863. Here, the heavily fortified Confederate Fort Wagner was located. The fort had been under Union bombardment for more than a day. Colonel Shaw met with General Strong and learned that there would be a frontal assault on Wagner that night. The General asked Shaw if the 54th would like to lead the attack. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw replied, “Yes”. Before joining his men, Colonel Shaw located Edward L. Pierce, a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune and gave him some letters and personal items to pass on to Shaw’s family if he was killed.

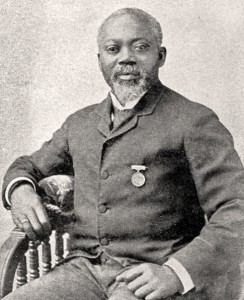

on July 6 and asked that the 54th Massachusetts be placed under his command. This occurred a few days later and the regiment performed very honorably in its first major engagement at James Island, South Carolina on July 16. Shortly after the battle, the 54th began a two day excursion with only the hardtack they carried in their packs for food. Marching through mud flats and marsh, through thunderstorms and in the blazing sun, with the aid of two transports they made it to Morris Island on the afternoon of Saturday, July 18, 1863. Here, the heavily fortified Confederate Fort Wagner was located. The fort had been under Union bombardment for more than a day. Colonel Shaw met with General Strong and learned that there would be a frontal assault on Wagner that night. The General asked Shaw if the 54th would like to lead the attack. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw replied, “Yes”. Before joining his men, Colonel Shaw located Edward L. Pierce, a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune and gave him some letters and personal items to pass on to Shaw’s family if he was killed.The assault on Fort Wagner would begin at dusk. Six Hundred soldiers from the 54th Regiment gathered less than 1,000 yards from the fort and waited. The 54th would lead the first wave of the assault while white troops from Connecticut, New York and New Hampshire regiments would follow in a second wave. What none of the men could have known at that time is the Union bombardment of the fort had been ineffective and its garrison of 1,700 Confederate soldiers would still be fighting at full strength. Both General Strong and Colonel Shaw addressed the men. Shaw encouraged the 54th saying, “I want you to prove yourselves. The eyes of thousands will look on what you do tonight.” At about 7:45 pm, Colonel Shaw stood at the front of his regiment and gave the command to advance at the quick-step. The men had their bayonets fixed and they knew the fort must be taken in hand-to-hand combat. With the Atlantic Ocean to the right and a creek on the left, the 54th moved along a narrow strip of beach and Shaw ordered the pace to double-quick while still some distance away. When they were about 100 yards out, the Confederate soldiers from Fort Wagner began firing with such ferocity that the 54th started to hesitate. But Colonel Shaw rallied the men and led a group of them through a ditch and to the top of the parapet. He was one of the first to climb the walls of the fort. Here, as he waved his sword and urged his men forward, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw was shot in the chest and fell into the fort. When the flag bearer for the regiment was killed, Sergeant William Carney of New Bedford, Massachusetts grasped the flag and soon planted it on top of the parapet and held it there as the troops scaled the walls. In this detailed account, Carney mentions that he was shot several times during his attempt to prevent the flag from being captured by the enemy. When he reached the Union lines, Carney staggered into a hospital and amidst the cheers of his fellow soldiers – both black and white – told them, “Boys, I but did my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground.” He then collapsed from his wounds.

Following the battle, the Confederate commander of Fort Wagner buried Colonel Shaw in a pit with some of his black soldiers in an attempt to dishonor him. When Shaw’s parents learned this, it had the opposite effect. They said there could be no holier place than where he lies surrounded by his brave soldiers and requested that no attempts be made to recover his body. Of the 600 members of The 54th Massachusetts that led the first wave of the assault on Fort Wagner, nearly half made their way into the fort. Two hundred seventy two were either killed, wounded or captured. The charge had certainly proven the courage of black troops under fire and the bravery of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and his fellow officers. Of the assault, even a Confederate officer named Iredell Jones could not help but proclaim, “The Negroes fought gallantly, and were headed by as brave a colonel as ever lived.” The story of Colonel Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts is told in the must-see 1989 movie Glory. In the film, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw is played by actor Matthew Broderick.

but Johnson Hagood below said different

After defeating Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment at the second Battle of Fort Wagner, commanding Confederate General Johnson Hagood returned the bodies of the other Union officers who had died, but left Shaw's where it was, using the logic of most Confederate officers that the African American soldiers were fugitive slaves and that the attack of the fort was a slave revolt led by Shaw. Hagood informed a captured Union surgeon that ordinarily his body would have been released for burial, but as was the case, "We buried him with his niggers.After the war, Hagood resumed planting, but became incensed by the alleged misrule and corruption of Radical Republicans during Reconstruction. He actively campaigned for fellow Confederate general Wade Hampton in the 1876 gubernatorial contest and himself was elected on the Democratic state ticket as Comptroller General. He served a term until 1880 when he was nominated by the state Democrats for Governor. Hagood easily won the gubernatorial election that fall and his major achievement in office was the reopening of The Citadel in 1882.Hagood died in Barnwell and was buried at Episcopal Churchyard. For his loyalty and commitment to The Citadel, Johnson Hagood Stadium was named in his honor. Hagood, South Carolina is named for him, as well as several streets throughout South Carolina.

On Memorial Day in 1897, during the ceremonies unveiling Saint-Gaudens magnificent memorial to Shaw and the 54th, sixty-five veterans of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment marched at the head of the parade. Among those veterans, carrying the American flag, was Sergeant William Carney. Three years later in 1900 his heroic efforts under fire to save the flag would finally be recognized when, nearly 37 years after the assault on Fort Wagner, Carney became the first African American to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. That Memorial Day in 1897, Sergeant Carney and his fellow veterans marched along the same route they had taken when they left Boston on May 28, 1863. This time, however, they traveled in the opposite direction, symbolically meeting and honoring their fellow soldiers and their leader Colonel Shaw – men who had not lived to see the lasting impact they had made.

Three years later in 1900 his heroic efforts under fire to save the flag would finally be recognized when, nearly 37 years after the assault on Fort Wagner, Carney became the first African American to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. That Memorial Day in 1897, Sergeant Carney and his fellow veterans marched along the same route they had taken when they left Boston on May 28, 1863. This time, however, they traveled in the opposite direction, symbolically meeting and honoring their fellow soldiers and their leader Colonel Shaw – men who had not lived to see the lasting impact they had made.

Three years later in 1900 his heroic efforts under fire to save the flag would finally be recognized when, nearly 37 years after the assault on Fort Wagner, Carney became the first African American to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. That Memorial Day in 1897, Sergeant Carney and his fellow veterans marched along the same route they had taken when they left Boston on May 28, 1863. This time, however, they traveled in the opposite direction, symbolically meeting and honoring their fellow soldiers and their leader Colonel Shaw – men who had not lived to see the lasting impact they had made.

Three years later in 1900 his heroic efforts under fire to save the flag would finally be recognized when, nearly 37 years after the assault on Fort Wagner, Carney became the first African American to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. That Memorial Day in 1897, Sergeant Carney and his fellow veterans marched along the same route they had taken when they left Boston on May 28, 1863. This time, however, they traveled in the opposite direction, symbolically meeting and honoring their fellow soldiers and their leader Colonel Shaw – men who had not lived to see the lasting impact they had made.

No comments:

Post a Comment